There is a paradigm shift in progress these days in corporate governance. It is going mainstream to the extent that major global business and political leaders advocate a change in the existing corporate model. The new paradigm is about moving from shareholder capitalism to stakeholder responsibility, from short-term to long-term thinking. All eyes are put on CEOs to integrate the environment, society and good governance as a measured part of corporate accountability. Which de facto puts CEOs on the tricky situation to engage, not only shareholders, but all the stakeholders of their organizations. This is no more and no less than the efforts to deliver for companies to get their license to operate and secure their future.

The late 20th century’s celebrated mantra that “the business of business is business” no longer brings money. In the late 1970s, Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman started to popularize the idea that a corporation is only responsible for increasing shareholder value. In his view, executives work for the owners (shareholders) and a company’s sole responsibility is to increase its profits. For decades, business schools, consulting and investment firms have been spreading Friedman’s words. This theory is still prevalent today and it would be premature to say that the primacy of shareholders is over. But a growing number of thought leaders is voicing that socially responsible organizations can benefit society and shareholders simultaneously.

The recent natural cataclysms in Australia, Amazonia or Siberia, as well as the current COVID-19 pandemic, may have accelerated the pace of general awareness. But it is more likely the growing pressure on companies from consumers and employees to become proactive common-good enablers that prompted forward-thinking leaders to put both the planet, people and profit at the top of their agendas.

Departing from Friedman’s position, US academics Michael Porter and Mark Kramer argued in 2011 that companies capable of leveraging on corporate social responsibility could make a difference. By addressing societal needs, they create value for their customers, employees, their communities, and ultimately their investors. Shareholder economy, based on and the bottom line and investor financial requirements, is gradually giving way to stakeholder capitalism. In stakeholder capitalism, corporations are oriented towards serving the interests of all their stakeholders.

Joe Biden, in his speech on Economic recovery Plan , 9 July 2020.

The concept is not new, but it has gained momentum as a criticism of neoliberalism negative impacts on natural and social capitals. Its proponents, such as the New-Keynesian economist Joseph Stiglitz, believe that it should replace shareholderism as a principle of corporate governance. The World Economic Forum Davos agenda has been calling for years for more resilient, inclusive and sustainable economies, including through the engagement of all stakeholders. Stakeholder capitalism even recently invited itself to the 2019 Business Roundtable. In the words of its then Chairman Jamie Dimon, who is also chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., “major employers are investing in their workers and communities because they know it is the only way to be successful over the long term”.

Running a company with a multi-stakeholder approach obviously entails more risks to mitigate, more expectations to meet, and more impacts to assess.

Business and reputation risks. Studies show that companies affected by environmental, social, and governance (ESG) controversies underperform. Société Générale precisely found that share value could underperform the broader stock market by an average of 12% over 2 years after “high ESG controversy” events. From bribery and corruption to workplace discrimination and environmental incidents, corporate scandals can have significant financial repercussions ranging from legal penalties to consumer boycotts. In addition, these incidents damage the reputation of both the companies themselves and their shareholders.

More expectations to meet. All stakeholders’ eyes are on CEOs, expecting their companies to contribute to long-term, shared value creation. 76% of respondents to the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer say that CEOs should initiate change, rather than wait for governments to impose it. Fears about hyper-globalization, automation, artificial intelligence or gig economy are real. Many say they believe the public sector is not doing enough to protect people, their jobs and well-being; they expect business leaders instead to take action.

Not taking into account these new realities exposes the companies and their CEOs to new forms of activism with potentially strategic consequences. At GE’s 2021 general meeting for instance, the CEO’s remuneration was rejected by the majority of shareholders. Similarly, DUPONT chemical company leadership has been asked by a group of shareholders led by As You Sow to measure the group’s plastic pollution to align on competitors practices. Under Share-action activism, Tesco has pledged to increase healthy food proportion in its sales from 2022, to fight obesity.

For decades, the sole financial responsibility of companies has been scrutinized in the light of profitability and shareholder value maximization. But the time has come when public opinion considers that companies are primarily responsible for the impact on their global ecosystems, regardless of when and where they operate, produce, invest and recruit.

In a multi-stakeholder capitalism approach, business leaders are accountable for financial performance as well as for the value they generate or destroy to their customers, employees, suppliers, investors, regulators, the environment, communities, etc. Paying fair wages, ensuring safety in the workplace, providing good customer service, investing in local communities, preventing environmental damage are some examples of commitment to stakeholder capitalism.

In a multi-stakeholder capitalism approach, business leaders are accountable for financial performance as well as for the value they generate or destroy to their customers, employees, suppliers, investors, regulators, the environment, communities, etc. Paying fair wages, ensuring safety in the workplace, providing good customer service, investing in local communities, preventing environmental damage are some examples of commitment to stakeholder capitalism.

Advocacy and demand for stakeholder capitalism is at its peak, pulling companies in a deep transformation journey. But its implementation needs watchfulness from business leaders to drive their organization on the path of long-term value strategies. A key factor of success lies on engaging stakeholders proactively around the company’s mission and strategy and building trust relationships with them.

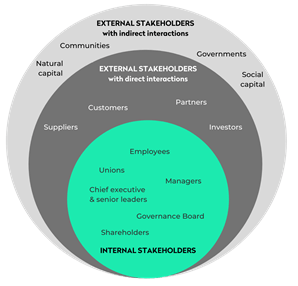

The first step towards stakeholders engagement is to define who your stakeholders are. There is a widely shared definition of the stakeholder concept in ISO 26000 international standard for corporate social responsibility.

ISO 26000

Following ISO 26000 recommendations, you can identify groups of stakeholders with different needs or interests. According to the potential impact your company’s global activities or specific decisions can produce, you may chose to foster dialogue with some of your stakeholders while further involving others in the design and implementation of your social responsibility programs.

A step-by-step approach to engage your company’ stakeholders can be as follows:

- start identifying your stakeholders

- map their respective needs and interests and analyse the risks of not meeting such needs

- focus on strategic risks to mitigate them (ie, the risks that could have critical consequences on the financial health, strategic path, leadership, short term or long-term viability of your organization)

- involve your stakeholders in the design and implementation of your sustainability roadmaps

- be transparent towards your stakeholders and report regularly on the impacts on them

- commit to correct negative impacts and grasp the opportunity to create positive impact

Ultimately, change your corporate governance guidelines if needed. Not an easy task, but sooner or later it will be seen as the counterpart to the license to operate now and in the future.